The Press and the People: Cheap Print and Society in Scotland/ 1500-1785 | Adam Fox

The Press and the People | Detalhe de capa

Early modern Scotland was awash with cheap print. Adam Fox, in the first dedicated study of the phenomenon in Scotland, gives readers some startling figures. Andro Hart, one of Edinburgh’s leading booksellers, died in 1622. In his possession, according to his inventory, were 42,300 unbound copies of English books printed on his own presses. John Wreittoun, also Edinburgh based, had in stock at his death in 1640 what Fox estimates to be 7,680 ‘waist littell scheittis of paper’, printed up as ‘littell pamphlettis and balladis’, and averaging a sale price of just 3d Scots (pp. 70-2). The inventory of Robert Drummond, drawn up, again in Edinburgh, in 1752, recorded a quantity of printed ‘small phamphlets’ and ‘ballads’ that Fox estimates amounted to 174,000 separate copies ready to go to market (p. 107). While historians of early modern print are well aware that the number of works we know about was once far surpassed by those now no longer extant, Fox’s examination of the inventories of Scotland’s printers and booksellers confirms the scale of the loss. It shows that Scottish printers were not predominantly producers of books and exposes a ‘vastly’ larger market for cheap print ‘than has ever been realised’ (p. 11).

Although Fox’s engaging book surveys the development of Scottish printing from its origins in the early sixteenth century, it is the period from the later seventeenth to the end of the eighteenth century that attracts most attention. This is not surprising, since it is evident that the print trade underwent significant growth across these decades. ‘Progress was sometimes intermittent and slow’, but the evidence suggests that, from 1660, ‘something like a national “popular literature”’ was evolving. Some 19,000 imprints emanating from Scottish presses survive for the century between 1660 and 1760, but twice as many were produced in the second half of the period than in the first (p. 49). Numbers involved in the book trade also increased. Over 300 individuals can be identified as printers, booksellers, stationers, and bookbinders by the 1750s, some ten times the number known for the mid-seventeenth century (p. 51). Edinburgh, despite increased competition from rivals Glasgow and Aberdeen, remained the dominant centre for print in Scotland and second in Britain after London. Surviving titles from Edinburgh presses rose from around 3,000 works in the quarter-century before 1700, to roughly 10,500 between 1761 and 1790 (p. 99). As we will see, the period also witnessed a broadening of the range of genres and forms available to Scottish readers: the market was not, as the stereotype of Calvinist Scotland might have it, exclusively given over to bibles and catechisms.

The book is in two parts. Part I examines the components necessary to the creation of a mass market for cheap print and tracks the development of the book trade, first in Edinburgh, then in other burghs. While Rab Houston has long since questioned whether Scotland enjoyed unusually high levels of literacy in the early modern era, expanding educational provision and the Kirk’s promotion of reading skills as a means of Protestantising the people undoubtedly resulted in the ability to read becoming increasingly commonplace amongst the labouring population.(1) Print also had to be available in sufficient quantities and cheaply enough for ordinary people to get sight of it. Fox asserts that print in Scotland was under a ‘strict regime of regulation and censorship’ (p.45), exercised by the privy council, the main organ of secular government in Scotland, the institutions of the church, and the councils that ran the major burghs. His argument is that the system worked with ‘varying degrees’ of success, until expanding output pushed the authorities into shifting attention away from the effort to license all titles, towards the targetting of material deemed unsuitable for public consumption (p. 46).

Scotland did not, however, have an equivalent of the London Stationers’ Company, a commercial monopoly that, by the reign of Elizabeth, had secured its privileges in return for taking on the responsibility of regulating the trade. The Company extended its reach into Scotland, although it had no authority in a separate kingdom, in order to prevent Scottish presses becoming a conduit for cheaper foreign productions into England. Here some reflection on the fact that the coveted position of King’s Printer was in the hands of the Company from 1632 until the early 1670s would have been welcome. How did the Company’s presence in Scotland during this turbulent forty-year period affect the indigenous print trade? It is likely that the consequences were higher costs and less competition.(2) The waning of the Company’s influence might usefully have been considered alongside the evidence presented in later chapters for the expanding availability of more kinds of cheap print.

In the second part of the book, Fox turns his attention to varieties of cheap print. Although Fox acknowledges that handbills and placards were used to convey ‘the latest intelligence’ on weighty matters of national interest (p. 236), the bulk of the discussion is dedicated in this chapter to the writing of elegies, the popularity of which Fox ascribes in part to simple ‘entertainment’ (p. 248), and the advertisement of goods and services, such as medical remedies, auctions, and theatrical and musical performances. Last words and dying speeches overlapped with elegies, but they rightly receive more detailed treatment in a dedicated chapter, as much for what Fox contends they can reveal about popular attitudes to crime and the law as for the instruction that educated elites thought the populace ought to get about such matters. The eclecticism of all this fare is further reinforced by an important chapter on ballads and songs, which have received limited attention due to the paucity of survivals. As with other forms of cheap print, ballads often originated in England and circulated either as imports or as reprints from Scottish presses. From the 1670s, English material was supplemented by an increasing stock of ‘native ballads’ (p. 320).

Two further chapters, on almanacs and prognostications and on ‘story books’ (chapbooks), offer amongst the first extended scholarly treatments of these particular forms of print. Both types ‘followed the lead’ of England, but took on their own distinctively Scottish characteristics (p. 395). Alamanacs were common throughout Europe and the Scottish varieties covered, naturally enough, much the same type of material. Fox draws attention both to the important role of Aberdeen, especially through the press of Edward Raban, in the early development of the genre, and to the useful local information that became an important feature of later alamanacs. The subject matter of Scottish chapbooks ranged widely across the religious and the secular. Although the former covered well-established topics such as the nature of sin, conversion narratives, and examples of extraordinarily pious lives, they also reflected, and enabled, the persistence of popular identification with the Covenanting tradition of the 1640s. The histories, verse narratives, chivalric epics, and jests that made up Scotland’s ‘merry and entertaining’ (p. 408), and frequently bawdy, story books simultaneously sustained the nation’s own vernacular literary traditions, while familiarising Scottish readers with English tales that have remained popular on both sides of the border into the modern age.

How did people encounter cheap print? Much of this material was ‘of a “public” nature – proclamations, notices, news items – and thus they were intended to be cried in open spaces, posted on prominent buildings, and hawked around communal resorts.’ (p. 187) Most of the evidence presented for what Fox terms ‘street literature’ pertains to Edinburgh and to the century or so after the Restoration. Fox shows us a vibrant urban environment almost quite literally papered with ephemera of many kinds. Lively poems could be bought from the criers and enjoyed at leisure in one of Edinburgh’s half dozen coffeehouses, where the consumer could show off his (less likely her?) purchase to other regulars. His friends would flourish the latest copy of a newsletter from London and ask whether he had seen the new edition of the Edinburgh Gazette. Advertisements carried by criers, posted on the walls of coffeehouses and, later, included in newspapers point both to the commercialisation of Scottish society and to a wider associational culture of ticketed plays and performances. Although not discussed in detail, the implication here is that, despite losing parliament and privy council in the early eighteenth century (but not, crucially, its law courts), Edinburgh retained the atmosphere of a capital city at least in part because it continued to be a national hub for the production, consumption, and dissemination of news and information.

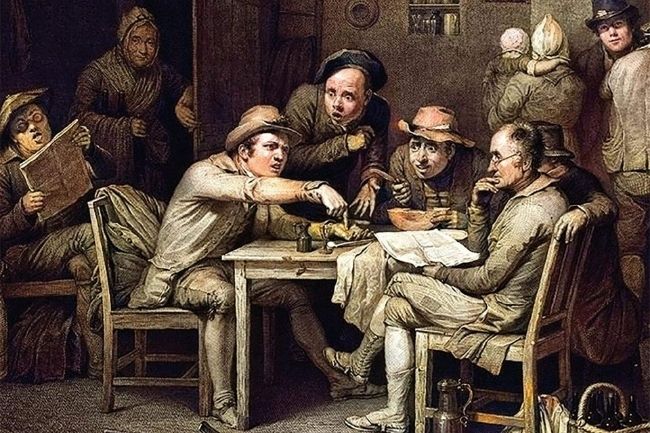

The book concludes with reference to the artwork that adorns its jacket. David Wilkie’s Village Politicians (1806) depicts ‘country workers’ discussing the content of a newspaper. We deduce for ourselves that these men are capable of engaging with political ideas and conducting an informed debate. Fox sees this scene as emblematic of developments that had ‘transformed the nation’ over the previous two centuries. What were they? ‘Religious turmoil and political crisis’ were part of this process, but so was quickening economic activity and urban expansion. The result was a ‘new kind of public sphere’. Print enabled ‘public opinion and a popular culture’ to emerge (pp. 429, 431). There was more to say here on precisely how the genres and forms discussed by Fox brought a ‘public sphere’, ‘public opinion’, or a ‘popular culture’ into being. In what ways did the expansion of cheap print shape and reflect changes in the characteristics of Scotland’s public or popular cultures over the centuries?

Historians of early modern Scotland have often sought to explore politics and religious controversy through study of the interactions between ‘official’ print, such as proclamations and state oaths, and what might be termed polemical or propagandistic output. Such material is not the primary focus of this book. Although Fox gives readers a good sense of a vibrant world of print consumption, especially in the major urban centres, there is very little elaboration about either the economic and commercial developments that were driving the expansion of cheap print, or what the increasing availability and accessibility of this material might tell us about a changing socio-economic order. Wilkie’s painting, produced in an age of revolution, has been read as a statement on the emergence of a new political consciousness amongst labouring Scots and, when first exhibited in 1806, it caused a sensation in consequence. What would happen if we put these same figures in attire appropriate to the mid-sixteenth century and swapped the newspapers for the ballads of the Protestant propagandist, Robert Sempill? The latter’s work, which features in Fox’s book (pp. 7, 60, 308-13), claimed to speak for common Scots, but did it speak to them? In other words, did the sort of people to whom the educated Sempill gave voice actually read his productions? Stray complaints, mostly from the church authorities, about the people’s love of profane songs and ballads hints at popular engagement with the printed word in the century before the civil wars. What had most obviously changed between the era of Sempill and that of Wilkie was the sheer abundance and variety of the material that common Scots could now access.

Did the expansion of cheap print create a shared culture underpinned not only by familiarity with the same stories, news, and information, but also by the practice of reading itself? There were certainly people who were not included in such a culture. The lengthy list of illustratrations – the publishers are to be commended on this score – references two ballads whose subject was a ‘Highland laddie’, but contains no examples of a work printed in the Gaelic language. As Fox acknowledges, the ‘popular culture’ of print was a Lowland one (p. 431). Was it also essentially the culture of men? Fox flags up the ‘instrumental role played by women’ in the printing and book trades (p. 13), most notably the formidable Agnes Campbell (d.1716). Female literacy was on the rise and, as is well known, more women were able to read than write. We might further contend that the availability of a widening range of genres, regardless of the stereotyping and misogynistic tropes, was partly informed by awareness of the existence of a female readership. Possible barriers to the inclusion of women, especially those of the lower orders, are not discussed by Fox. Women’s opportunities for socialising in spaces where print was available were more limited than men’s. (Women ran Edinburgh coffeehouses, but the depiction of a coffeehouse clientele by eighteenth-century artist Paul Sandby shows only men). Women’s wages were lower than those of men and, while they commonly took responsibility for household budgets, we might question whether wives and daughters had the autonomy to spend on whatever they chose. It is perhaps telling that the two women in Wilkie’s painting are not involved in the debate going on around the newspaper. One has been to fetch beer for the company, while the other has her back to the viewer and is clutching an infant.

Fox’s study suggests further questions both about who engaged with particular kinds of print and what that might tell us about Scotland before the Industrial Revolution. Speaking particularly of almanacs, Fox’s mention of a widening distinction between ‘the expensive books of the learned classes and the cheap print of the majority’ (p. 384) echoes Peter Burke’s ‘little’ and ‘great’ traditions, in which the people, unlike the educated elite, participate only in the former. Elsewhere in the book, Fox suggests a more subtle interpretation, in which printers facilitated the popularising of literary classics by putting them into smaller, lower-quality and, hence, more affordable formats (pp. 395, 411). It seems unlikely that the transformation of George Buchanan, Renaissance scholar and the sternest of tutors to James VI, into a jesting storyteller had the consequence of generating demand for his political works. Yet his belated and rather improbable popularisation perhaps says something notable about how common Scots understood their own history. As Fox wants to make clear, the ubiquity throughout this period of material either imported directly from England or derived from English sources and reprinted on Scottish presses did not simply turn Scotland into a satellite of the London print market (not least because Scots continued to import material from Continental and especially Dutch publishing houses). It is evident that Scottish presses, run in the main by Scottish men and women, served to develop and diversify ‘a print culture that was distinctively Scottish’ (p. 11): material was sometimes composed in Scots vernacular, featured Scottish characters and narratives, detailed information about places and events in Scotland, and attended to matters of Scottish interest. This was not, in Fox’s view, incompatible with a print culture marked at all levels, he claims from before 1603, by a ‘certain “Britishness”’ (p. 433).

Although there is no further elaboration on this point, it seems clear that Fox is proposing the existence of overlapping Scottish and British cultures of print. However, while Fox can chart some of the traffic of English print into Scotland, Scottish productions heading the other way are beyond the scope of the book. The shared elements of this ‘British’ print culture are therefore English characters like Robin Hood and King Arthur. One way of nuancing Fox’s interpretation might, therefore, look like this: from at least the middle of seventeenth century, London increasingly determined the character of print production and consumption throughout the archipelago but, in the process, left space for, and indeed further stimulated, regional markets with their own distinctive features. Whatever conclusions readers draw from this carefully researched study, they will be indebted to Adam Fox for opening up rich new seams of material and proposing new possibilities for a fuller understanding of Scottish society and culture in the pre-modern age.

Notes

1 R.A. Houston, ‘The literacy myth? Illiteracy in Scotland 1630-1760’, Past & Present 96 (1982), 81-102.Back to (1)

2 Laura A.M. Stewart, Rethinking the Scottish Revolution: Covenanted Scotland, 1637-51 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2016), 36.Back to (2)

Resenhista

Laura A.M. Stewart – University of York.

Referências desta Resenha

FOX, Adam. The Press and the People: Cheap Print and Society in Scotland, 1500-1785. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020. Resenha de: STEWART, Laura A.M. Reviews in History. Londres, n. 2457, mar. 2022. Acessar publicação original [DR]