Posts com a Tag ‘Soldiers/ Saints/ and Shamans: Indigenous Communities and the Revolutionary State in Mexico’s Gran Nayar/ 1910–1940 (T)’

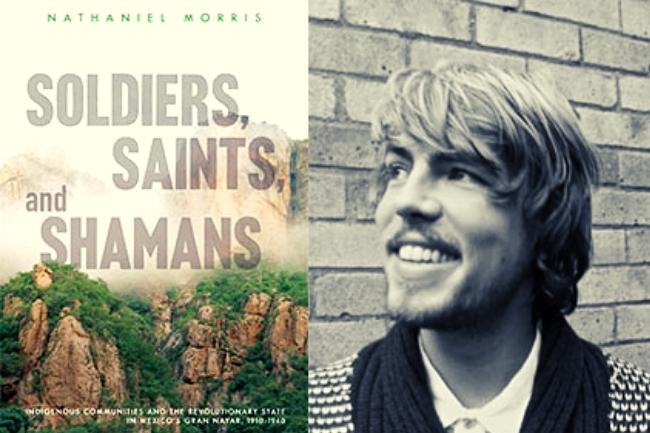

Soldiers, Saints, and Shamans: Indigenous Communities and the Revolutionary State in Mexico’s Gran Nayar, 1910–1940 | Nathaniel Morris

Nathaniel Morris | Imagem: The University of Arizona Press

The period 1910-40 was tumultuous in Mexican history. The armed phase of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) was followed by fragmented attempts by Revolutionary politicians to assert Federal control and modernisation in the face of military rebellion, resistance to social reform, two major religious revolts known as the Cristiada, and ongoing, albeit often unremarked, agency from Mexico’s indigenous populations. This latter aspect is the focus of research in Nathaniel Morris’s excellent new history. The author’s specific attention is on the Wixárika, Naayari, O’dam, and Mexicanero communities of the Gran Nayar region along with adjoining locations along the Sierra Madre Occidental highlands.

Nathaniel Morris’s work is a landmark study of ethnohistory and a highly original addition to our knowledge of Mexico’s revolutionary and counter-revolutionary era of 1910-1940. His focus is the Gran Nayar, a region centred on Nayarit, but also including parts of the states of Sinaloa, Jalisco, Zacatecas, and Durango, during the armed phase of the Mexican revolution and the Cristero wars. Soldiers, Saints and Shamans fills a void in the historiography. As Morris correctly points out, there has been very little historical analysis of indigenous agency in the Mexican Revolutionary period, and ‘the Gran Nayar remains entirely absent from most Mexicans’ mental map of the period’ (p. 11). Throughout the 19th century, any Indian initiative was written off as a ‘caste war’, and irreconcilable with White and mestizo nation-building.(1) 20th-century historians and anthropologists mostly assumed that Mexico’s indigenous populations were either passive recipients of Revolutionary nation-building schemes or defiant outsiders from the mestizo state. A landmark study of caudillos (political/military ‘strongmen’) in the Independence Wars represented Indians as ‘apolitical’.(2)) Indigenous agency was usually explained as a defence of ‘old ways’, and the amorphous collection of rituals, everyday representations, and beliefs lumped together as a static rather than dynamic ‘costumbre’ (customs). Condescending, and even racist, interpretations died hard, as Nathaniel Morris’s separate study of the 19th-century Manuel Lozada revolt in a similar region has shown.(3) The outsized role played by indigenous communities in religious revolts, including the Cristiada, was explained as being motivated by religious devotion and an ingrained scepticism towards the Mexican state.(4) More recent scholarship has shifted the dial somewhat, demonstrating the considerable degree to which indigenous peoples collaborated with White/mestizo state-building all the same, often by turning against their defiant (‘bronco’) kin.(5) But Soldiers, Saints and Shamans should be considered a breakthrough. Leia Mais