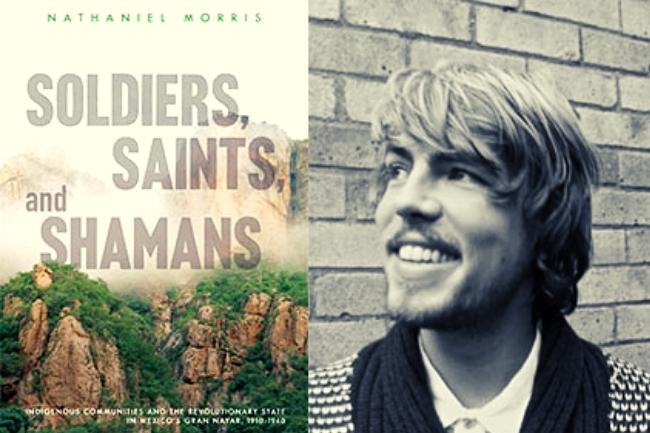

Soldiers, Saints, and Shamans: Indigenous Communities and the Revolutionary State in Mexico’s Gran Nayar, 1910–1940 | Nathaniel Morris

Nathaniel Morris | Imagem: The University of Arizona Press

The period 1910-40 was tumultuous in Mexican history. The armed phase of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) was followed by fragmented attempts by Revolutionary politicians to assert Federal control and modernisation in the face of military rebellion, resistance to social reform, two major religious revolts known as the Cristiada, and ongoing, albeit often unremarked, agency from Mexico’s indigenous populations. This latter aspect is the focus of research in Nathaniel Morris’s excellent new history. The author’s specific attention is on the Wixárika, Naayari, O’dam, and Mexicanero communities of the Gran Nayar region along with adjoining locations along the Sierra Madre Occidental highlands.

Nathaniel Morris’s work is a landmark study of ethnohistory and a highly original addition to our knowledge of Mexico’s revolutionary and counter-revolutionary era of 1910-1940. His focus is the Gran Nayar, a region centred on Nayarit, but also including parts of the states of Sinaloa, Jalisco, Zacatecas, and Durango, during the armed phase of the Mexican revolution and the Cristero wars. Soldiers, Saints and Shamans fills a void in the historiography. As Morris correctly points out, there has been very little historical analysis of indigenous agency in the Mexican Revolutionary period, and ‘the Gran Nayar remains entirely absent from most Mexicans’ mental map of the period’ (p. 11). Throughout the 19th century, any Indian initiative was written off as a ‘caste war’, and irreconcilable with White and mestizo nation-building.(1) 20th-century historians and anthropologists mostly assumed that Mexico’s indigenous populations were either passive recipients of Revolutionary nation-building schemes or defiant outsiders from the mestizo state. A landmark study of caudillos (political/military ‘strongmen’) in the Independence Wars represented Indians as ‘apolitical’.(2)) Indigenous agency was usually explained as a defence of ‘old ways’, and the amorphous collection of rituals, everyday representations, and beliefs lumped together as a static rather than dynamic ‘costumbre’ (customs). Condescending, and even racist, interpretations died hard, as Nathaniel Morris’s separate study of the 19th-century Manuel Lozada revolt in a similar region has shown.(3) The outsized role played by indigenous communities in religious revolts, including the Cristiada, was explained as being motivated by religious devotion and an ingrained scepticism towards the Mexican state.(4) More recent scholarship has shifted the dial somewhat, demonstrating the considerable degree to which indigenous peoples collaborated with White/mestizo state-building all the same, often by turning against their defiant (‘bronco’) kin.(5) But Soldiers, Saints and Shamans should be considered a breakthrough.

Soldiers, Saints and Shamans draws on unused archives, conversations with veterans and their descendants, and on ethnographic research, to produce a remarkable analysis, all amidst the challenges posed in this region by the ongoing drugs war. Dr Morris has lived with host communities and sensitively interprets conflicting oral history testimonies, while maintaining the rigour of the historian. Readers will feel for themselves the intimacy of these sources, as well as the natural confusion made between elderly eyewitnesses and descendants regarding particular chronologies, risings, and battles. The author sanely makes a disclaimer as to his own fallibility. But the result is as objective as can be reasonably hoped. Morris avoids the condescending and romanticised biases of earlier anthropologists. The millenarianism which cloaked most comments on pre-Columbine populations’ religious and political practices is here explained. Morris shows an excellent grasp of indigenous metaphysics. Indian responses to the Revolution and the Cristiada in the Gran Nayar were a sophisticated expression of local power politics. Revolutionary reforms, such as the government-appointment of headmen of O’dam communities, threatened a meta-apocalypse, according to the O’dam worldview. These reforms destroyed the spatial rather than linear perception of time, and would result in a catastrophic failure of the rains. But Morris shows how Indian communities were not solely metaphysical in their calculations. They also reacted as logically as mestizos to the pendulum swings of armies and the threats and opportunities these posed.

Thus, Morris explains how fiercely independent indigenous communities used external initiatives to consolidate their own interests. The O’dam of Durango were amongst the least Catholic people in Mexico, if the presence of priests is anything to go by. Yet they were amongst the most enthusiastic Cristeros of the 1920 and 30s. Federal threats to ancestral lands and costumbre made the anti-Federal Cristero revolt a convenient vehicle for defending local interests. Here, Jean Meyer’s model of popular, rather than elite, agency in the Cristero rebellion religious militancy in the Cristiada is revised further. Religion, or at least Catholicism, comes as a close second, if that, in motivations. Morris’s work develops the findings of other regional studies in Mexican history which, over the past 30 years, have stressed peripheral and horizontal agency in matters of reform in land, religion, and education. Some local elites backed the Federal government, using paramilitary militias (defensas) as a vehicle for their ambition, whereas others backed revolts, especially the Cristiada, relying on forced conscription rather than the faithful voluntarism of legend. The fact that this indigenous region had long remained peripheral to Liberal and Revolutionary nation-building projects meant that both defensas and Cristeros were empowered in the national political crises of 1926-29, and the 1930s.

Morris also shows how indigenous communities clung to the very costumbre which had historically defined them. The indigenous communities ‘traditionalised’ the Revolution, in the same way that post-Columbine Indians incorporated and parodied Catholic rituals into their original religious fiestas (p. 266). After three decades of intra- and inter-communal violence, and the encroachments of the mestizo state, the 1940s found the Gran Nayar in a state of despondent cynicism. Indigenous attitudes towards any authority figures connected with external revolution and counter-revolution, whether priests, teachers, government officials, or caciques, were poisoned for generations.

There are definitely a few jagged edges and discontinuities in the writing. However, this is never a boring read. Dr Morris has produced a vital text for understanding the Mexican Revolution and its aftermath from the perspective of indigenous populations. Dr Morris should be congratulated on bringing clarity and interest to this neglected aspect of history, and the work should be strongly recommended to any serious scholar of modern Mexico.

Notes

1 In Mexico, the term mestizo (lit. “mixed”) is used to refer to an identity of those of mixed European (mainly Spanish) and indigenous Mexican descent.Back to (1)

2 John Lynch, Caudillos in Spanish America, 1800-1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 134.Back to (2)

3 Nathaniel Morris, Manuel Lozada, la ‘leyenda negra’, y el nacimiento del agrarismo en la conformación de Nayarit (Tepic: Consejo Estatal para la Cultura y las Artes de Nayarit, 2017).Back to (3)

4 E.g. Edwin Lieuwen, Mexican Militarism, the Political Rise and Fall of the Revolutionary Army, 1910-1940 (New York: Praeger, 1981), p. 84. Back to (4)

5 Julia O’Hara, ‘The Slayer of Victorio Bears his Honors Quietly’, in Nicola Foote and René D. Harder Horst (eds.), Military Struggle and Identity Formation in Latin America: Race, Nation and Community During the Liberal Period (University of Florida Press, 2010), pp. 224-242.Back to (5)

Bibliography

Lieuwen, Edwin, Mexican Militarism, the Political Rise and Fall of the Revolutionary Army, 1910-1940 (New York: Praeger, 1981)

Lynch, John, Caudillos in Spanish America, 1800-1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991)

Morris, Nathaniel, Manuel Lozada, la ‘leyenda negra’, y el nacimiento del agrarismo en la conformación de Nayarit (Tepic: Consejo Estatal para la Cultura y las Artes de Nayarit, 2017).

O’Hara, Julia, ‘The Slayer of Victorio Bears his Honors Quietly’, in Nicola Foote and René D. Harder Horst (eds.), Military Struggle and Identity Formation in Latin America: Race, Nation and Community During the Liberal Period (University of Florida Press, 2010), pp. 224-242.

Resenhista

Mark Lawrence – University of Kent.

Referências desta Resenha

MORRIS, Nathaniel. Soldiers, Saints, and Shamans: Indigenous Communities and the Revolutionary State in Mexico’s Gran Nayar, 1910–1940. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2021. Resenha de: LAWRENCE, Mark. Reviews in History. Londres, n. 2463, aug. 2022. Acessar publicação original [DR]