Posts com a Tag ‘Guerra Civil’

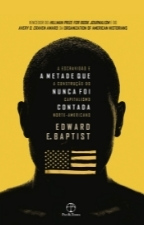

A metade que nunca foi contada: a escravidão e a construção do capitalismo norte-americano | Edward Baptist

Edward E. Baptist | Foto: nytimes.com

O autor Edward Baptist é professor da Universidade de Cornell e historiador dos Estados Unidos, tendo o século XIX como recorte cronológico. Estuda a vida de homens e mulheres escravizados no Sul, região que é cenário de uma maciça expansão da escravatura, devido à lucratividade do algodão (o que terminou por precipitar a Guerra Civil em 1861). O público a que o livro se destina é aquele que deseja conhecer melhor a força da escravidão, por um lado, e, por outro, também a força dos escravizados. Também mata a sede de quem quer entender o contemporâneo apego dos estadunidenses ao lado perdedor da guerra, o sulista, que quis se separar do país para fundar um outro, a fim de manter a escravidão. Os efeitos duradouros desse apego podem ser simbolizados hoje, mais do que nunca, nas imagens da tentativa de golpe de Estado em 6 de janeiro de 2021, a qual, embora um fiasco, conseguiu desfraldar a bandeira confederada dentro do Capitólio. Leia Mais

Unredeemed Land: An Environmental History of Civil War and Emancipation in the Cotton South – MAULDIN (THT)

MAULDIN, Erin Stewart. Unredeemed Land: An Environmental History of Civil War and Emancipation in the Cotton South. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. 256p. Resenha de: SCHIEFFLER, G. David. The History Teacher, v.52, n.4, p.720-722, ago., 2019.

Erin Stewart Mauldin’s Unredeemed Land is the latest addition to the vast body of literature that explains how the Civil War and emancipation transformed the rural South. Whereas previous scholars have highlighted the war’s physical destruction, economic consequences, and sociocultural effects, Mauldin, an environmental historian, examines the profound ecological transformation of the Old South to the New. Using an interdisciplinary methodological approach, she argues that the Civil War exacerbated southern agriculture’s environmental constraints and forced farmers—“sooner rather than later”—to abandon their generally effective extensive farming practices in favor of intensive cotton monoculture, which devastated the South both economically and ecologically (p. 10).

Mauldin contends that most antebellum southerners practiced an extensive form of agriculture characterized by “shifting cultivation, free-range animal husbandry, slavery, and continuous territorial expansion” (p. 6). Although the South’s soils and climates were not suitable for long-term crop production, most farmers circumvented their environmental disadvantages by adhering to these “four cornerstones” (p. 6). Ironically, however, these very practices made the South especially vulnerable to war. When the Civil War came, Union and Confederate soldiers demolished the fences that protected southern crops, slaughtered and impressed roaming livestock, razed the forests on which shifting cultivation and free-range husbandry hinged, and, most significantly, destroyed the institution of slavery on which southern agriculture was built. Mauldin’s description of the Civil War’s environmental consequences echoes those of Lisa M. Brady’s War Upon the Land (2012) and Megan Kate Nelson’s Ruin Nation (2012), but with an important caveat: in Mauldin’s view, the war did not destroy southern agriculture so much as it accelerated and exacerbated the “preexisting vulnerabilities of southern land use” (p. 69).

After the war, southern reformers and northern officials urged southern farmers, white and black, to rebuild the South by adopting the intensive agricultural practices of northerners—namely, livestock fencing, continuous cultivation, and the use of commercial fertilizers as a substitute for crop and field rotation. Most complied, not because they admired “Yankee” agriculture, but because the “environmental consequences of the war—including soldiers’ removal of woodland, farmers’ abandonment of fields because of occupation or labor shortages, and armies’ impressment or foraging of livestock—encouraged intensification” (p. 73). Interestingly, many southerners initially benefited from this change. Mauldin contends that the cotton harvests of 1866-1868 were probably more successful than they should have been, thanks to the Confederacy’s wartime campaign to grow food and to the fact that so much of the South’s farmland had lain fallow during the conflict. In the long run, however, this temporary boon created false hopes, as intensive monoculture “tightened ecological constraints and actively undermined farmers’ chances of economic recovery” (p. 73). Mauldin argues that most of the southern land put into cotton after the war could not sustain continuous cash-crop cultivation without the use of expensive commercial fertilizers, which became a major source of debt for farmers. At the same time, livestock fencing exacerbated the spread of diseases like hog cholera, which killed off animals that debt-ridden farmers could not afford to replace. Finally, basic land maintenance—a pillar of extensive agriculture in the Old South—declined after the war, as former slaves understandably refused to work in gangs to clear landowners’ fields and dig the ditches essential to sustainable farming. Tragically, many of those same freedpeople suffered from planters’ restrictions of common lands for free-range husbandry and from the division of plantations into tenant and sharecropper plots, which made shifting cultivation more difficult. And, as other scholars have shown, many black tenants and sharecroppers got caught up in the crippling cycle of debt that plagued white cotton farmers in the late nineteenth century, too.

Mauldin’s story of the post-war cotton crisis is a familiar one, but unlike previous scholars, she shows that the crisis was about more than market forces, greedy creditors, and racial and class conflict. It was also about the land. Despite diminishing returns, southerners continued to grow cotton in the 1870s, not only because it was the crop that “paid,” but also because ecological constraints, which had been intensified by the war, encouraged it. Instructors interested in teaching students how the natural environment has shaped human history would be wise to consider this argument. They should also consider adding “ecological disruptions” to the long list of problems that afflicted the New South, as Mauldin persuasively argues that the era’s racial conflict, sharecropping arrangements, and capital shortages cannot be understood apart from the environmental challenges that compounded them (p. 9).

In the 2005 Environmental History article, “The Agency of Nature or the Nature of Agency?”, Linda Nash urged historians to “strive not merely to put nature into history, but to put the human mind back in the world.” With Unredeemed Land, Erin Stewart Mauldin has done just that and, in the process, has offered one way in which history teachers might put the Civil War era back in its natural habitat in their classrooms.

David Schieffler – Crowder College.

[IF]Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management – ROSENTHAL (THT)

ROSENTHAL, Caitlin. Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019. 312p. Resenha de: MUHAMMAD, Patricia M. The History Teacher, v.52, n.4, p.724-725, ago., 2019.

Scholars have written extensively concerning the Trans-Atlantic slave trade’s intricate financial regime promoted through multi-lateral treaties, slaving licenses, nation states, private companies, and slavers, proprietors, and bankers who financed and insured this barter in human commodities. In Accounting for Slavery, Professor Caitlin Rosenthal outlines municipal slavery business structures primarily in the West Indies; with slaveowners at the highest rank, followed by overseers and attorneys who were property managers. Using the terms “proprietor,” “balance,” “tally,” “middlemen,” and “employees,” Rosenthal transposes this verbiage with “plantation owner,” “bottom line,” “slaves,” “skilled workers,” “overseer,” and “watchmen”—demonstrating the level of accounting practices slaveowners developed.

Interlaced with technical nomenclature, the author includes historical events that affected plantation operations, such as the Maroon Rebellion in Jamaica and more frequent occurrences of sabotage of production output and plots to escape slavery’s brutality. She furthers her analysis by discussing crimes against humanity such as branding and torture as false incentives to increase labor production and compliance. Thus, enslaved people were forced to work against their will and were also chastised for fighting against a system in which human rights violations were systemically committed against them.

The author also discusses how slave codes encouraged plantation owners to maintain accurate records of their slaves’ whereabouts. Local authorities fined slaveowners for failure to abide by these laws, which only complemented their accounting practices. Both municipal and transnational law reflected Europeans’ desire to maintain control of their extended empire through hierarchies that negotiated with established Maroon communities of formerly enslaved people.

Although these communities were not acknowledged as a nation state, they had authority to enter a bi-lateral treaty with England in 1739 to preserve their autonomy with a condition precedent to not accept any additional runaway slaves.

Rosenthal then examines the impact of absentee proprietorship, in which plantation owners returned from the West Indies to England, seeking to maintain accountability of both land and slave. Consequently, these slavers authored plantation manuals (accounting guidelines) to track slaves, harvest, land, and productivity, referred to as “quantification.” Arguably, these standards were the financial antecedent to generally accepted accounting practices used to evaluate professional standards of modern bookkeeping for Western corporations. The slavers also furthered transnational law through lobbying with the British Parliament, securing their interests in sugar markets and a form of anti-dumping preventative measures under international trade law, as well as opposing the nascent trend in public international law to abolish the slave trade. The author argues that their records had a mitigating effect on the regulation of plantation slavery enforced by local officials, requiring slavers to adhere to graduated punishments that they recorded as evidence in their own defense.

Thereafter, Rosenthal dissects the methodology of plantation accounting, including ledgers, balance sheets, sticks used by slaves to account for livestock tallied annually, and eighteenth-century slaveowners’ advent of pre-formatted forms and double bookkeeping. These written records became evidence for British abolitionists to use against West Indian slavers since they not only detailed the loss of productivity, but also the loss of slaves’ lives resulting from the violence and torture they bore at the hands of slave masters.

Rosenthal then assesses rating systems based on historical records that affected the price of slaves as further evidence of their commodification. For instance, she employs the usage of “depreciation” in relation to an enslaved person’s decline due to disobedience, age or health. Value and (human) capital reinforced the disparity of rights between the enslaved and the master, with one person determining the other person’s worth based on what could be extracted by force or used as collateral for purchase of other tangible property.

Lastly, the author discusses the effects of the Civil War and Reconstruction on both slavers and enslaved. Slavers had the ability to quit the land and negotiate.

However, the agreements enslaved people signed were usually under duress, and former slaveowners had a greater bargaining position due to literacy, land ownership, prior financial gain from their former slaves, and the use of black codes to keep freed peoples subordinate.

The author uses primary sources to illustrate the development of accounting practices, through organization, law, and politics, making the text valuable for historians and graduate students specializing in those matters. With assiduous care, Rosenthal successfully depicts municipal slavery’s evolution from scattered processes to maintain control of slaves and land into a sophisticated, individual business venture that documented crimes against humanity and ironically supported the institution’s inevitable extinction.

Patricia M. Muhammad – Independent Researcher.

[IF]

Magnífica e Miserável: Angola desde a guerra civil | Ricardo Soares Oliveira

Magnifica e Miserável: Angola desde a guerra civil é um livro de autoria do investigador português Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, publicado originalmente em língua inglesa (Magnificent and Beggar Land: Angola since the civil war) e seis meses mais tarde dado à estampa pela editora portuguesa Tinta-da-China. A publicação desse livro provocou em certo entusiasmo incontido em alguns meios jornalísticos e acadêmicos em Portugal e o Reino Unido, que se manifestaram nos comentários qualificativos sobre o autor e a obra constantes na contracapa da versão inglesa, assim como da versão portuguesa tais como: “lúcido, brilhante” e “fascinante, provocativo”, por um lado, “profundo conhecedor da política do petróleo em Angola” e “melhor estudo sobre Angola em inglês”, por outro. Salvo engano, o livro mereceu algumas de resenhas críticas à versão inglesa1 que ampliam e levantaram a discussão sem que a mesma fosse sentida no meio acadêmico angolano e de língua portuguesa.

Magnífica e Miserável apresenta-nos uma capa que ilustra o pôr do sol da costa de Luanda e os escombros do mausoléu, obra quase abandonada, infraestrutura imponente à soviética onde repousa os restos mortais do primeiro presidente de Angola independente, António Agostinho Neto. Esta ilustração sinaliza o que entendemos ser o início da representação caricatural, – da magnificência – que se pode encontrar reforçada no texto. Leia Mais

The War Within: new perspectives on the civil war in Mozambique/1976-1992 | Eric Mourier-Genoud, Michel Cahen, Domingos M. Rosário

Uma característica trágica compartilhada pela história nacional de alguns países africanos é a emergência de conflitos militares dentro de suas próprias fronteiras que, via de regra, estão marcados por uma combinação variável de fatores e atores internos e externos – de um lado, a explosão de tensões e clivagens sociais que o regime político implantado após a independência não foi capaz de resolver, e em alguns casos agravou; de outro, a incidência de interesses econômicos e geoestratégicos que condicionaram a participação de outros Estados, empresas multinacionais e órgãos multilaterais. Na década de 1960, essa dinâmica alimentou conflagrações sangrentas no Congo-Léopoldville, nos Camarões e na Nigéria; após a independência dos territórios africanos submetidos à dominação portuguesa, Angola e Moçambique viram seus nomes incluídos nessa malfadada lista. Em Moçambique, diferente de Angola, a hegemonia política e militar do novo regime demorou alguns anos a ser seriamente desafiada. Embora tenha havido uma resistência armada localizada na Zambézia desde 1976, foi a partir do início da década seguinte que uma situação de guerra interna se generalizou, prolongando-se até 1992, quando foi assinado o Acordo Geral de Paz. Leia Mais

Guerra Civil. Super Heróis: Terrorismo e Contraterrorismo nas Histórias em Quadrinhos | Victor Callari

Pouco explorada pelos historiadores, as fontes iconográficas ganharam nesses últimos anos um espaço de destaque no cenário historiográfico. As mudanças de perspectivas desenvolvidas no decorrer do século XX e também no início do XXI possibilitaram uma ruptura com leituras tradicionais que restringiam o trabalho do historiador aos arquivos e seus documentos considerados oficiais, e abriram espaços para novos questionamentos, abordagens e metodologias que ampliaram significativamente as possibilidades de compreensão de eventos passados e da contemporaneidade. A entrada dos historiadores nesse ramo diversificou ainda mais as produções acadêmicas. Autores conhecidos do grande público, como Peter Burke, Ivan Gaskell, Carlo Ginzburg, entre outros, se aventuraram em obras com essa abordagem, e se tornaram referências no âmbito acadêmico. Por outro lado, pesquisadores em início de carreira também vêm se aventurando e promovendo, mediante suas pesquisas, uma expansão significativa nesses estudos, muitos deles partindo de objetos até então pouco explorados pela historiografia.

Foi nesse novo cenário que a Editora Criativo publicou a obra “Guerra Civil. Super Heróis: Terrorismo e Contraterrorismo nas Histórias em Quadrinhos” (2016), resultado da dissertação de mestrado realizada dentro do Programa de Pós-Graduação em História e Historiografia da Universidade Federal de São Paulo – Unifesp, sob orientação da professora Drª Ana Nemi, escrita por Victor Callari professor da rede particular tanto no Ensino Superior quanto na Educação Básica. Callari possui publicações em periódicos acadêmicos nacionais e participações em eventos internacionais, em temas relacionados às histórias em quadrinhos, memória, holocausto, terrorismo, entre outros assuntos pertinentes a sua área. Leia Mais

This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy – KARP (PR-RDCDH)

KARP, M. .This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016. 360p. Resenha de: CAPRICE, K. Panta Rei. Revista Digital de Ciencia y Didáctica de la Historia, Murcia, p. 187-188, 2018.

In This Vast Southern Empire, Matthew Karp steps back from the previous historiography of the slaveholding antebellum South, a historiography that situates slaveholders as antiquated and inward looking, and, instead, Karp sees a slaveholding Southern elite looking outward in an attempt to enshrine their vision of modernity: a world economy run on slave labor. Karp bookends his study with the 1833 British emancipation of the West Indies, seen by Southerners as a global threat to the proliferation of slavery, and the creation and ultimate failure of the Confederate States of America, which Karp deems the “boldest foreign policy project of all” (p. 2). In this fresh take, Karp argues that, from 1833 to 1861, Southern elites eagerly utilized Federal power to secure the safety of slavery, not just in the United States, but throughout the Western Hemisphere.

By looking globally, Karp provides new and broader understandings to events previously seen as having only insular motivations. American interest in Cuba was less about the expansion of American slavery, Karp argues, and more about blocking the expansion of British anti-slavery, what Karp brilliantly terms as the “nineteenth-century domino theory” (p. 70). In a similar vein, Karp shows that Polk’s decision to push for war with Mexico, while pursuing peace with Great Britain over the Oregon question, was at least partially due to the fact that war with Mexico would not put the institution of slavery at risk. Insights from Karp’s global perspective do not end with the antebellum period, but extend into the policies of the Confederate government. As Karp explains, the immediate Confederate abandonment of the states’ rights platform was presaged by the Southern embrace of Federal power during their antebellum reign over American foreign policy. Through his argument, Karp provides yet another nail in the coffin which so securely holds the myth that the Civil War was fought for states’ rights rather than slavery.

In the epilogue, Karp closes by considering the imperialism of the 1890s as merely a continuation of the Southern elite’s original vision. Karp’s assessment, one deserving of far greater treatment, provides a steady timeline of white supremacy, framed originally as pro-slavery, and its position as the driver of American foreign policy. Previous views of the antebellum South as outmoded and inflexible, Karp makes astoundingly clear, dangerously underestimate a sectionalist dream of modernity with global reach. Along with a new understanding of the South, Karp also reframes the antebellum period, providing a transtemporal reassessment of the period typically considered “the coming of the Civil War.” Karp reimagines the early nineteenth century South as a growing slave empire from 1833 onward, an empire which required Republican success in politics and Union victory in war to overthrow, an assessment that is as imaginative as it is successful.

In the field of Civil War studies, which can at times view national borders as opaque and impassable, Karp’s work may be seen as so concerned with looking outward that it obscures the internal, but such criticism would be short sighted. Karp is adding to a historiography which is more than adequately saturated with examinations of the domestic struggles that eventually brought about war. David M. Potter’s 1977 The Impending Crisis, for example, is widely considered a masterwork on the coming of the Civil War, and it was certainly not the first or last published on the subject. Karp’s voice is a welcome addition, and his arguments should help convince many in the field to look beyond the black box in which we occasionally place ourselves while studying the Civil War.

Kevin Caprice – Purdue University.

[IF]Os Dois Lados da Guerra Civil: análise histórica e filosófica do maior conflito entre super-heróis | Bruno Andreotti

Este texto visa resenhar o livro Os dois lados da Guerra Civil: análise histórica e filosófica do maior conflito entre super-heróis, lançado em março de 2016 pela editora paulista Criativo. Escrito pelos “Quadrinheiros”, grupo formado por Adriano Marangoni, Bruno Andreotti, Iberê Moreno e Maurício Zanolini, o livro aborda a saga quadrinística da Guerra Civil, lançada pela editora Marvel entre os anos de 2006 e 2007, e trazendo, como o próprio título sugere, uma discussão historiográfica em torno das conexões culturais, políticas e sociais trazidas pela saga, cuja temática envolve um conflito entre super-heróis americanos decorrente de uma medida governamental exigindo o registro compulsório dos mesmos junto ao governo, que dividiu os heróis.

O livro, em suas 207 páginas, está dividido em seis capítulos principais, uma introdução e uma conclusão, e em alguns chamados “extras”, incluindo um glossário e uma interessante análise estética do traço dos desenhistas da saga. Um prefácio do professor Antonio Pedro Tota (PUC/SP) introduz a obra, apresentando os autores e os temas que serão abordados no livro. Leia Mais

Ganarse el cielo defendiendo la religión. Guerras civiles en Colômbia / Luis J. O. Mesa

O grupo de pesquisa Religión, Cultura y Socieáad, criado em 1998 em Medellín quando ali se realizou o X Congresso de História da Colômbia, propõe-se pensar historicamente os problemas da sociedade colombiana segundo padrões universais de conhecimento, partindo de perspectivas culturais, com ênfase nas manifestações religiosas. Considerando que as guerras e a Igreja Católica constituem duas chaves decisivas para a compreensão histórica, como fatores de longa duração operando no centro da lenta, gradual e violenta formação nacional do país, o grupo criou a linha de pesquisa “Guerras civis, religiões e religiosidades na Colômbia, 1840- 1902”. Ganarse el Cielo… é parte e resultado de uma série de atividades acadêmicas de pesquisadores colombianos e estrangeiros, privilegiando abordagens voltadas para as sociabilidades, vida cotidiana, iconografia, literatura, educação, memórias, recrutamento, eleições e formas de religiosidade, e indagando de que maneira indivíduos e grupos sociais viveram esta longa seqüência de guerras civis, como participaram, como as interpretaram, escreveram e representaram.

No preâmbulo, Diana L. Ceballos Gómez pergunta: por que a Colômbia parece irremediavelmente mergulhada no conflito? Por que, pelo menos desde o último quarto do século XIX, aí ocorre o emprego desmedido da força, dos meios políticos violentos, contrastando com a relativa estabilidade da maior parte dos países latino-americanos? Por que a violência parece ser o sangrento fio condutor da história colombiana? Após resenhar várias tentativas de resposta a tais angustiantes questões, Diana Ceballos indica a tipologia das guerras civis proposta por Peter Waldmann e Fernando Reinares como um instrumento a ser levado em conta.1 Entre 1830 e 1902, houve em território colombiano 9 grandes guerras civis generalizadas e 14 guerras localizadas; e, desde o assassinato do dirigente liberal Jorge Eliecer Gaitán, em abril de 1948, há guerrilhas em atividade no país.

No primeiro capítulo, “Guerras civiles e Iglesia católica en Colômbia en la segunda mitad dei siglo XIX”, Luis Javier Ortiz Mesa sistematiza teorias e concepções da guerra e da guerra civil, faz um balanço dos estudos sobre guerras civis e Igreja na formação da nação colombiana, e conclui com uma interessante comparação entre duas maneiras de fazer a guerra, contrapondo as regiões do Cauca (capital: Popayán) e Antioquia (capital: Medellín). As guerras civis e a intolerância religiosa foram fatores de polarização entre os colombianos e de exclusão de aspirações de grupos sociais cujos projetos de vida (“comunidades vividas”, cf. Eric Van Young2) não foram incorporados na formação das “comunidades imaginadas” pelas elites; mas, contraditoriamente, assim mesmo foram duas chaves de construção e integração do Estado e da Nação. A guerra é destruição, mas também é simultaneamente construção,3 e é festa de morte e de vida: Festa da comunidade finalmente unida pelo mais entranhado dos vínculos, o indivíduo finalmente dissolvido nela; capaz de dar tudo, até sua vida. Festa de poder-se afirmar sem sombras e sem dúvidas diante do inimigo perverso, de crer ingenuamente ter a razão, c de acreditar ainda mais ingenuamente que podemos dar testemunho da verdade com o nosso sangue.

A comparação entre os modos de fazer a guerra no Cauca e em Antioquia é particularmente interessante. Popayán, berço dos célebres caudilhos rivais Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera e José Maria Obando, foi o foco mais ativo das guerras civis até 1876, quando passam a triunfar na guerra os conservadores apoiados no modelo político da Regeneração e na profissionalização do exército. No Cauca, centro da mineração de ouro no período colonial, em crise desde a segunda metade do século X V I I I , a quebra dos laços de sujeição dos escravos e dos índios, a desarticulação do eixo hacienda-mina, a fragmentação regional — ascensão de Cali, proliferação de novos municípios no Vale do Cauca, expansão das fronteiras internas – favoreceram a emergência da guerra como meio de vida para muitas milícias de gente subalterna dispostas a acompanhar velhos ou novos caudilhos, geralmente de corte liberal. A sociedade antioquenha, com grupos de intermediação mais amplos e dotados de melhores condições econômicas e sociais (garimpeiros, pequenos e médios comerciantes, tropeiros, rede escolar mais extensa), era mais coesa e sua composição socio-racial mais homogênea que a caucana; seus circuitos comerciais articulavam eficazmente a mineração, a agricultura e a pecuária. Aí predominaram o conservadorismo, a Igreja e a família nuclear, e a guerra se fazia somente até certos limites, evitando-se maiores riscos de devastação, saques e endividamento.

No segundo capítulo, “La Constitución de Rionegro y el Syllabus como dos símbolos de nación y dos banderas de guerra”, Gloria Mercedes Arango de Res trepo e Carlos Arboleda Mora examinam o liberalismo radical da Constituição de 1863 e o integrismo do Syllabus do papa Pio IX, de 1864, como as duas modalidades possíveis de construção do Estado-Nação e da modernidade na Colômbia do século XIX: nação-cristandade ou nação liberal; modernidade tradicionalista, teocêntrica, controlada pelo clero, ou modernidade liberal, antropocêntrica, autônoma e legalmente ordenada. As divergências acerca da liberdade religiosa, do casamento civil, da presença dos jesuítas, da tutela estatal dos cultos, da desamortização, da educação laica, etc, começam com a independência, radicalizam-se no período 1861-1885 (separação entre a Igreja e o Estado) e quase silenciam por muitas décadas a partir de 1886/1887 (Regeneração e Concordata). A Colômbia vive ainda hoje sob o peso opressivo de um imaginário social extremamente belicoso, difundido pelos órgãos de imprensa do século XIX, que estigmatiza e exclui o opositor, tomado não como adversário, mas como um inimigo a abater.5 Também aqui, a comparação entre Antioquia e o Cauca é muito elucidativa.

Diana Luz Ceballos Gómez analisa, no capítulo 3, a iconografia colombiana das guerras civis do Oitocentos, dialogando com a perspectiva antropológica de Jack Goody sobre a imagem.’ Um CD-Rom com um conjunto precioso de imagens e de mapas históricos acompanha o livro. Juan Carlos Jurado Jurado trata de “Soldados, pobres y reclutas en Ias guerras civiles colombianas” e “Ganarse el cielo defendiendo la religión. Motivaciones en la guerra civil de 1851”. Seguem alguns estudos de caso sobre a guerra de 1876: Margarita Árias Mejía, “La reforma educativa de 1870, la reacción dei Estado de Antioquia y la guerra civil de 1876”; Paula Andréa Giraldo Restrepo, “La percepción de la prensa nacional y regional de Ias elecciones presidenciales de 1875 y sus implicaciones en la guerra civil de 1876”; Gloria Mercedes Arango de Restrepo, “Estado Soberano dei Cauca: asociaciones católicas, sociabilidades, conflictos y discursos político-religiosos, prolegómenos de la guerra de 1876”; e Luis Javier Ortiz Mesa, “Guerra, recursos y vida cotidiana en la guerra civil de 1876-1877 en los Estados Unidos de Colômbia”.

A última guerra civil do século X IX (1899-1902), conhecida como a Guerra dos Mil Dias, é abordada pelo viés das memórias publicadas por ex-combatentes em duas conjunturas distintas (início do século, conservador; anos 30, hegemonia liberal) por Brenda Escobar Guzmán. Ana Patrícia Ángel de Corrêa apresenta “Actores y formas de participación en la guerra vistos a través de la literatura”; Gloria Mercedes Arango de Restrepo destaca “Las mujeres, la política y la guerra vistas a través de la Asociación dei Sagrado Corazón de Jesus. Antioquia, 1870- 1885”. O volume se completa com um ensaio de Carlos Arboleda Mora sobre o pluralismo religioso na Colômbia.

Esta obra coletiva do grupo de pesquisa “Religión, cultura y sociedad” de Medellín, sobre a religião e as guerras civis do século X IX colombiano, é mais uma indicação da excelente qualidade da historiografia colombiana contemporânea, que acompanha as inquietações das demais disciplinas das ciências humanas e de toda a sociedade a propósito do problema crônico da violência. Além de Bogotá, que concentra o maior número de cursos universitários, pesquisadores e editoras, a historiografia acadêmica produzida em três capitais de departamentos: Medellín, Barranquilla e Cali, se destacam com maior visibilidade e merecem melhor divulgação no exterior. Sem maior espaço para prolongar esta resenha, cabe assinalar que os autores de Ganarse el cielo têm o privilégio de contar entre seus modelos de vida (e não somente de trabalho intelectual) com dois brilhantes historiadores precocemente desaparecidos: Germán Colmenares (1938-1990) e Luis Antônio Restrepo Arango (1938-2002).

Notas

1. WALDMANN, Peter e REINARES, Fernando (orgs.) Sociedades en guerra civil. Conflictos violentos de Europa y América Laúna. Barcelona: Paidós, 1999.

2. VAN YOUNG, Eric. Los sectores populares en el movimiento mexicano de independência, 1810-1821. Una perspectiva comparada, em URIBE URÁN, Victor Manuel e ORTIZ MESA, Luis Javier, (orgs.), Naciones, gentesj territórios. Ensayos de historia e historiografia comparada de América Latina y el Caribe. Medellín: Editorial Universidad de Antioquia, 2000.

3. Esse tema é tratado em detalhe no capítulo 10 por Luis Javier.

4. ZULETA, Estanislao. Elogio de la dificultady otros ensayos. Cali: Sáenz Editores, 1994.

5. V. a este respeito ACEVEDO CARMONA, Darío. La mentalidad de Ias elites sobre la violência en Colômbia (1936-1949). Bogotá: El Âncora, 1995.

6. GOODY, Jack. Contradicciones j representaciones. La ambivalência hacia Ias imágenes, el teatro, la ficción, Ias relíquias y la sexualidad. Barcelona: Paidós, 1999.

Jaime de Almeida – Universidade de Brasília

ORTIZ MESA, Luis Javier et ai. Ganarse el cielo defendiendo la religión. Guerras civiles en Colômbia, 1840-1902. Medellín: Universidad Nacional de Colômbia, 2005. Resenha de: ALMEIDA, Jaime. Textos de História, Brasília, v.13, n.1/2, p.245-249, 2005. Acessar publicação original. [IF]

The Black Book of Bosnia: The Consequences of Appeasement – MOUSAVIZADEH (CSS)

MOUSAVIZADEH, Nader. The Black Book of Bosnia: The Consequences of Appeasement. New York: Basic Books, 1996. 219p. Resenha de: TOTTEN, Samuel. Canadian Social Studies, v.35, n.2, 2001.

The Black Book of Bosnia is comprised of four parts: The Legacy of the Balkans which explores the history of ethnic strife and ethnic sanity in the Balkans, exposing the myth of eternal conflict and explaining the origins of this particular conflict (xii); A People Destroyed which highlights the accounts of hatred, sorrow, and the despair of the ordinary men and women engulfed in the war (xiii); Indecision and Impotence which analyzes the conflict in strategic and political terms ( xiii); and, The Abdication of the West which is comprised of a series of editorials and basically constitutes a call for action and a chronology of outrage (xiii). Each of these book reviews and articles appeared in The New Republic magazine between October 1991 and October 1995.

While the essays and book reviews in Part I are relatively long (between eight and a half to seventeen pages) and detailed, the articles in the rest of the volume are shorter in length (an average of about 3 pages). The former are ideal for homework assignments, while the latter could be read and discussed during a single class period.

The book is packed with revelatory information. In addition to the history of the Balkans, the many topics addressed include the formation and dissolution of Yugoslavia; the background, beliefs and relationships of the major players (Serbs, Muslims, and Croats) in the area; the multifaceted nature of the current strife; the various ethnic cleansings and genocidal actions and who committed them; and the inaction of and appeasement by the Western powers. A host of personal stories also provide powerful insights into various aspects of the conflict. For example, when a Muslim man, whose girlfriend is a Croat, was informed by an American reporter that it was dubious as to whether the U.S. would come to Bosnia’s rescue, the young man said, Maybe we should discover oil (73). Speaking about the fact that the West allowed tens of thousands of Muslims to be killed by the Serbs, a former prisoner of the Serbs said, If 100, 000 animals of some special breed were being slaughtered like this, there would have been more of a reaction (85). Such insights should resonate with most students.

The major drawback of the volume is the limited attention given to the various and horrendous human rights violations committed by the Muslims and Croats. The main focus, by far, is on the intentions and actions of the Serbs. However, as scholar Steven L. Burg (1997) notes: Croat forces carried out expulsions, internment, killing and atrocities against Muslim civilians who were victimized because they were Muslims (430) and, Muslim forces committed violations similar to those of the Croats during the period of the Croat-Muslim war of 1993. There is also evidence of persistent abuses of Serb civilians (430). Thus, teachers using this volume will need to seek out newspaper articles, essays, and first-person accounts that do not flinch from the fact that the Croats and Muslims were not altogether guiltless vis–vis such concerns. Teachers will also need to obtain information about the on-going folly of bringing the perpetrators of genocide to justice.

Notes

Steven L. Burg. 1997. Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina? in Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons, and Israel W. Charney (eds). Century of Genocide: Eyewitness Accounts and Critical Views. New York: Garland Publishers, P 424-433.

Samuel Totten – University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

[IF]